2023

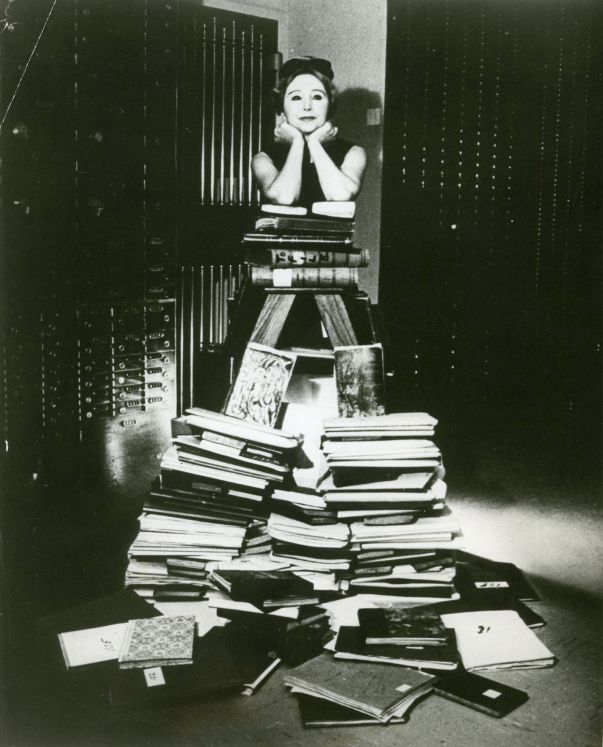

100+ Book Reviews Lost To The Ether

categories: bookish

If you read a book and write a review for it and share that review on the internet, but then those websites with your reviews close down or rebrand, and your work disappears… did it even happen?

This is something I’ve been struggling with for a while, and being a stubborn so-n-so, I have tediously scraped archive.org for my past work and have managed to compile over 100 book reviews – almost 25K worth of writing! See below for an absolutely massive collection of book reviews, originally posted between 2016-2020. They’re all out of order, chronologically, and I wouldn’t suggest you read this straight through, anyway. It’s a lot. There’s not a human person on Earth with that kind of attention span! Maybe just bookmark it to peruse at your leisure when you need a random recommendation. Maybe skim through and pick out a few things for your Goodreads list. Maybe you find a review that you vehemently disagree with and leave me a comment telling me so!

Do with this as you will!

Darkly: Blackness and America’s Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor Darkly was an illuminating, insightful read that gave me pause with every sentence. Part personal memoir, part cultural critique, part valuable history lesson, Taylor meditates on the Black experience and gothic culture through a collection of observations on music, film, art, philosophy, architecture, decay, and violence– and through these observations invites us to more closely analyze and question the aesthetics of those dark things we hold dear.

Something that struck me, in particular, is where Taylor asserts that: “goth is above all privileging the imagination over reason, choosing the fanciful over the pragmatic, forgoing restraint for excess,” and she further comments on the privilege of this frivolity and how this ostentatiousness is typically seen as a sentiment only for white people. That Blacks must be ever vigilant (due to the very justified paranoia that they can’t afford distraction) and therefore there’s this sense of gravitas or this sense of pride that they’re supposed to keep up and aren’t allowed strangeness or bizarreness. In this interview she brings up the phrase that gets tossed around, “What kind of White nonsense is that?” and further posits the often unasked question, that ”how is it that white people are allowed nonsense, but somehow Black people are not?”

The Woman In Cabin 10 by Ruth Ware. Eh. It’s a mystery-thriller from Ruth Ware. A journalist goes on a bespoke, luxury cruise, thinks she hears someone being thrown overboard in the next cabin and investigates the incident after being told there was no one actually staying in that cabin. You either like this sort of thing, or you don’t. I don’t think Ware’s efforts are necessary staples of the genre, but they are pretty fun whodunits, why-dunits, and maybe-even-youdunits. Like…I’d pay full price for them at an airport bookshop, but I’d leave it on my seat for the next passenger because I don’t see the need to make it a permanent addition to my bookshelf.

I think what I exceptionally don’t love are her characters, which typically seem to be people with messy lives that are in some fashion or another, either slowly or spectacularly, going to shit. Which hey, that could be any of us. I can’t be too judgy, I guess. But these individuals are annoyingly reckless and irresponsible (or at least they seem so to me, but I can be a little stodgy sometimes, and also maybe I see something in them that makes me feel very uncomfortable about how carelessly I behaved in my twenties) and there’s something …disagreeable about them that makes me not very sympathetic to whatever corpse-ridden mess they find themselves in. However. I’m on my library’s waitlist for the new title from this author so what do I know, anyway?

The Witch Elm by Tana French If Ruth Ware is the “eh it’s ok” of the psychological crime thriller authors, then I would venture to say that Tana French is one of the luminaries of the genre. What I enjoy most, I think, about French’s stories, is that neither the plots nor the perspectives/point of view take a predictable course, the characters don’t know each other or themselves very well, and even the detectives can’t necessarily be trusted. In The Witch Elm, Toby is a carefree, #blessed sort who doesn’t have to try very hard at anything and things just generally turn out okay for him with no effort on his part. Until…they don’t turn out very okay at all, after a home break-in, during which he is beaten to within an inch of his life. Struggling to recover from his injuries with the realization that he might never be quite the same again, he and his inexplicably rock-solid girlfriend move into his family’s ancestral home to care for his dying uncle Hugo. During an extended-family visit, a skull is discovered in the trunk of an elm tree in the garden and as the mystery deepens over the course of the investigation, Toby begins to consider the possibility that his past may not be exactly the way he remembers it.

The girlfriend was so weirdly loyal that I was halfway expecting/hoping for her to have somehow orchestrated the whole home invasion incident AND have been responsible for the decades-old murder, but that’s just my imagination running away with me, and I guess thank goodness no one is counting on me to solve any crime. I enjoyed the heck out of this story, and it’s interesting to note that the plot is inspired by a real-life tragic and grisly unsolved crime.

Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia I am not sure what I can say about this highly-acclaimed book that hasn’t been said. I mean it’s on everyone’s “best of 2020” lists for a very good reason. In 1950’s Mexico, a well-to-do young woman travels to an isolated estate to investigate her cousin’s frantic claims that her new husband is trying to kill her. A glamorous heroine who is tough, smart, and funny; the creeping decay and dread of an ancestral home in which resides some truly detestable and disgusting characters, disturbing dreams, ghosts that walk through walls, and a wonderfully interesting and super gross twist on the mechanics of the familiar haunted house trope. What’s not to like?

Ghost Summer by Tananarive Due In a similar “most likely to have all the things I like” vein, these engaging short stories by Tananarive Due tick every box for what I want in a summer read. (I think I read this in September, so that still counts, as far as I am concerned!) A vast spectrum of supernatural business, characters that I care about, masterful writing that is emotive and nuanced but not super dense or difficult. It’s got everything!

Dark Archives by Megan Rosenbloom Medical historian and biblio-adventurer Megan Rosenbloom’s investigation of books bound in human skin doesn’t just reveal details about the anthropodermic books, or the collectors who greedily hoarded them, or the craftspeople who created them; she passionately and humanely explores the people these books used to be. Along the way we learn of gentleman doctors in their mahogany-shelved libraries, flaunting strange collections; the gruesome and clandestine theatrics of midnight corpse-thieving grave robbers, midwives to royalty, 19th-century highwaymen in their final hours, poets and paupers, murderers and scientists–but as full as this book is of characters, Dark Archives provides an emotional examination that renders these pages, and I am quoting from The LA Times here, “…surprisingly intersectional, touching on gender, race, socioeconomics, and the Western medical establishment’s colonialist mindset.”

Come for the weird books facts, stay for the unexpected and powerful human questions. Additional questions, I might add, you can find answers for in our recent interview with the author!

Malorie by Josh Malerman. A Bird Box sequel exists. I read it. It was fine. Fast-paced, intense. It felt like it was missing something that I couldn’t quite put my finger on (maybe an extra 50 pages?) Maybe a bit rushed, sort a “direct to video” vibe. Also, like it was literally written for the screen. I finished it in the span of an afternoon, so I can’t say it didn’t keep my interest, but there are probably more interesting entries on this list. See directly below.

Bunny by Bunny Awad The less I say about this one, the better. It’s wild. One of the most imaginative things I have ever read. Dark and funny and wicked and perfect, and the setting is one with which I’ve developed a fair bit of a fixation. I have a peculiar fondness for characters deeply involved in high-level educational pursuits, especially in niche or obscure areas of study. I think it’s because I lived at home and worked crazy-stupid hours at a fast food restaurant while I attended community college classes–most of which I only showed up for half of the time because I have immense anxiety when it comes to classroom settings.

My failure to properly fulfill what I guess has been beaten into my brain as a sort of “All-American scholastic obligation” has led to a deep sense of shame about my lack of credentials* but has over time cultivated a deep and abiding fascination with the whole university experience– especially the weird sort of bubble that students who live on campus, who do not have to work to support themselves, and who are consumed with their research and studies, seem to exist in. Anyway, I did say I wasn’t going to divulge much about this book, and I did not! I mostly talked about myself! A bunch of Goodreads reviewers apparently thought it was too weird and it broke their poor, dumb brains, but if you revel in stories that elicit gleeful hisses of “whaaaaat the fuuuuuuck?!” then I am certain you will enjoy the bizarre delights of this wonderfully demented little gem.

*Which is not to say I am regretful about my lack of education in this context; I 100% do not wish to be saddled with decades of student debt, but I’ll admit to a certain insecurity about my lowly associates degree that took me the better part of ten years to obtain.

Where The Wild Ladies Are by Aoko Matsuda The stories in this collection are loosely based on traditional Japanese tales of yokai, the ghosts and monsters that figure prominently in the country’s folklore. At turns clever, tender, and empowering, and brimming with strange wonders coexisting with mundane, everyday scenarios, Where The Wild Ladies Are is a lighthearted and whimsical-bordering-on-absurdist exploration of these classic stories and the supernatural beings that cavort amongst them, through a contemporary, feminist lens.

Spectral Evidence by Trista Edwards I haven’t read much in the way of poetry recently…or any poetry in these last ten or eleven months at all, come to think of it. And if there was any year that we needed a breath of the poetic and sublime to transcend this timeline, even for the space of a moment or two–it is now.

I received this volume of poems and illustrations a few months ago, and I am working my way through the collection, each line aquiver with a predestined sadness, the tragedy of an unavoidable outcome that you’re determined to see through. These poems evoke the foreknowledge of the moment when everything changes, but how you keep marching toward it, and somehow even returning to it. To look backward on your innocence and forward toward your annihilation. How you can’t have it both ways, except when you can.

The Book of Horror: The Anatomy of Fear on Film by Matt Glasby Though I’m a life-long fiend for all things horror, my love for the genre does tend to wax and wane. Sometimes I become a bit unplugged, only to dive back in with a voracious ferocity that’s probably a bit alarming from an outsider’s perspective. Matt Glasby’s The Book of Horror: The Anatomy of Fear on Film, and has marvelously rekindled my love for all things horrid, haunting, and harrowing. Glasby examines some of the most frightening films created and explores with us what it is exactly, that makes them so scary. Which sounds like it might be a dry, scholarly affair, but it’s not even a bit! The analysis is tightly written, wryly humorous, and exceptionally insightful, and, coupled with the spare elegance of the striking black and white artwork—I’m utterly immersed and enthralled and I haven’t been able to put it down.

Foe by Ian Reid I can’t even believe that I read another book by this author. I was SO MAD when I finished I’m Thinking Of Ending Things, I wanted to throw it into the sea. But I am a fool and also a bit of a masochist, and when I saw that Reid had published a new title, I thought “why not?” This time, though, I went into it prepared, knowing that nothing is quite what it seems and that things may get twisty…

Junior and his wife, Hen live a sedate, solitary life on their farm, far from others. Just the two of them and their chickens. We learn that keeping livestock has been banned; through this and a few other subtle details, we realize that some things have happened and that the world Junior and Hen are living in is a little bit different than the one we inhabit.

A stranger unexpectedly shows up at their doorstep one evening to inform them that Junior has been selected to travel far away; in fact, he may be going into space to begin the installation of a new settlement. Hen does not seem especially unsettled or surprised by this shocking news. But this is not all. We later learn that to reduce the trauma of having an absent spouse, Hen will be provided with a replacement–someone who, while not exactly Junior, will be nearly indistinguishable from him–to keep her company, while he is away.

I went into this story knowing that I need to pay attention to what’s NOT being said, but also, to take exactly what is being said very, very literally. I don’t know if these tactics spoiled my feelings about the ending or not because I figured out exactly where the story was going long before it got there. Regardless, this is a riveting, immersive read and a tense, intrusive, and not entirely comfortable exploration of the intricacies of relationships and human nature/human consciousness. Again, I can’t believe I am even saying this… but I am insisting that you absolutely must read Foe.

What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City by Mona Hanna-Attisha is an account of the Flint water crisis by is the relentless physician who stood up to those in power in order to address a gross environmental injustice and save the city she loved. Dr. Hanna-Attisha writes compellingly, compassionately, and with such an intensity, that you feel like you’re there in the trenches with her, just trying to get somebody, anybody, to pay attention to her urgent findings of the elevated levels of lead in her tiny patients’ bloodstreams…

Alongside What The Eyes Don’t See, I read Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris by Christopher Kemp, and this, too, is a wonderfully gripping, engaging book–but in a very different way. Flint’s inhabitants, especially the children, need lead-free water for all kinds of important health and developmental reasons; that is a book about water, the vital role that it plays in our lives, and the unconscionable negligence on the part of the government to keep it safe. Floating Gold, however, follows one man’s obsessions and adventures concerning ambergris, a kind of disgusting substance that is basically impacted dung, forcefully expelled from a sperm whale and used at one time to flavor rich people’s food or as a component in posh fragrances. Ambergris is an astoundingly expensive ingredient, sometimes costing more per ounce than gold, and an element in certain luxury items for people who, I imagine, would never have to worry about lead in their water. That’s probably a sweeping generalization, but in comparing these two books–both about stuff happening in water, both fascinating and informative, yet in the end so very different–it’s a conclusion that I couldn’t ignore.

Adrift: A True Story of Love, Loss, and Survival at Sea by Tami Oldham Ashcraft I guess the inadvertent theme for this month was “water”? I saw the trailer for this film maybe half a dozen times earlier this year, and although my interest was slightly piqued by this story of love and loss and survival at sea, ultimately, I knew it was nothing I would ever sit and watch in a theatre. I probably wouldn’t even watch it if it was on Netflix and I didn’t have to leave the house. Movies like this (romance? adventure?) are generally not my cuppa. When I found out it was based on a book (originally titled Red Sky In Mourning), ah–well, that’s a different story, so to speak. It’s weird, but I’m totally okay with spending two days reading what I wouldn’t even consider spending two hours watching. Tami, an adventurous young woman and experienced sailor, meets and falls in love with Richard, an equally spirited, thrill-seeking guy. They set out from Tahiti to deliver a yacht to San Diego, and two weeks into their journey they find themselves in the midst of a catastrophic hurricane, during which Tami is knocked out while down below deck, and Richard is swept overboard. From there on it’s a 41-day day of survival, in a crippled boat, out in the middle of the Pacific ocean. With a whole bunch of flashback scenes to spice things up, because being stranded alone doesn’t actually make for exciting reading, I guess. Now, the movie trailer would have you believe certain things that you immediately find out are not true at all, if you are reading the story in the book. That’s all I’m going to say about that, because maybe you want to read this or watch the film, and I don’t want to spoil it entirely. I feel like an asshole after reading the glowing reviews; I can’t deny the author’s vast courage and resourcefulness, but I’m a picky reader, and something about the author’s tone and the way she told the story just…annoyed me. I think this book could have benefitted from a ghostwriter.

How to Be a Good Creature: A Memoir in Thirteen Animals Sy Montgomery Sy Montgomery is a naturalist and author with a great passion for animals and the world around us, whose words and voice and tone, unlike Tami Oldham Ashcraft above, I quite enjoy. I suppose that’s a little unfair; Tami Oldham Ashcraft was a sailor with a tremendous story to tell, but who, as far as I know, is not actually a writer; conversely, making words say things to connect with people is how Sy Montgomery earns a living. I guess she had better be good at it! In How To Be A Good Creature, she reflects upon thirteen animals, both of the commonplace and exotic variety, who affected her life in profound and surprising ways. It’s a very charming book, and while not exactly revelatory in the information it puts forth regarding the various creatures, it’s written very personally with a lot of heart, there are some lovely illustrations, and overall, it’s just a wonderfully sweet book. I do think this would be a perfect hexmas holiday gift for that dear animal-lover on your list.

Calypso by David Sedaris I discovered David Sedaris from the BPAL forums at just precisely the right time in my life. I was newly released from a two-week stay at, well, I don’t know what they call it in New Jersey– but in Florida, where I grew up, we always referred to it as the 1400 ward…or, I suppose, it is better known as “Behavioral Services”. Over a decade later, I still haven’t decided how I feel about calling it my reason for being there a “suicide attempt”, although from a certain perspective…or any perspective, really…I am not sure what else you could call it. At any rate, I was home again. And just as sad, and lonely, and miserable as before I left. The one thing getting me through the joyless gloom of my days were online interactions with my friends on the one forum on the internet that I felt most comfortable frequenting. I would often lose myself in various random threads on this online space for weird perfume oil enthusiasts , and in doing so, I found solace in various recommendations of the titles that some of these similarly bookish folks were currently reading. I checked out a few David Sedaris books from the library, and quite all at once, a great love–instant and utterly electrifying–was born. On so many levels I identified with his absurd stories of his deeply fucked up family and his bitter, clever, eccentric humor, and I can’t deny that laughing until I thought I might pee myself felt loads better than crying until I was hoarse and wishing I were dead. Calypso, his latest offering, is more of that same perverse intimacy and sardonic wit and biting observations (some so stark and cruel that you feel guilty for laughing, but you can’t help yourself), as he reflects on aging and mortality…and feeding tumors to turtles.

Angels of Music by Kim Newman. Kim Newman (Anno Dracula, etc.) is an author who I’ve been meaning to read for years now, but never got around to it until Angels of Music was thrust upon me by a well-meaning friend at a holiday party last month. Newman writes a heady brew of horror, crime, fantasy noir, and this title in particular combines a measure of each of these fantastical elements–imagine if you will, a Victorian Charlie’s Angels, as masterminded by The Phantom of the Opera. Written serial-style, the book comprises five separate adventures with a revolving door of familiar faces as the titular Angels–we spend time with such noted characters as Lady Snowblood, Eliza Doolittle, and Irene Adler as the Phantom’s team of elite female agents who repeatedly save Paris from diabolical masterminds. If it sounds ridiculous, well, it is, just a little. But you’ll be having too much fun with it to care.

Unspeakable Things: Sex, Lies and Revolution by Laurie Penny I am somewhat ashamed to say I have never been keen on reading non-fiction. Books are a means of escape for me, and I don’t fancy an escape to real-world problems, thank you very much. But I’m realizing more and more that our current social and political climate does not call for once-upon-a-times and fairy tales, and so I intend to fortify my knowledge and educate myself accordingly. Unspeakable Things is an excellent place to start: intensely personal and somewhat autobiographical, Penny writes unapologetically on gender and power and love and feminism in vivid, witty, com/passionate language; a cry for awareness, a challenge, and a call to arms, Unspeakable Things is a powerfully vital manifesto, and though not always a comfortable read, it should prove to be not too painful for non-fiction phobes.

The Hunger by Alma Katsu, a thrillingly creepy supernatural re-telling of that Donner Party business, peopled with vividly imagined characters, gripping, chaotic drama, and a gorgeously ghastly atmosphere of pervasive fear. And now I’m pretty sure that now you can’t convince me that this author’s vision of those terrible events aren’t exactly how it did happen those many years ago.

Experimental Film, by Gemma Files my friend Sonya mentioned this book some time ago, and I knew right away it was something I’d enjoy…and I did! A deeply strange but excellent story, a sort of pseudo-documentary, rich in history and myth and weird technical details, about a mystery many decades old and how it begins to seep into the life of the woman obsessed with it.

Final Girls by Riley Sager this was trashy vacation reading, hinging on that old “final girls” chestnut–you know, the girl who survived the brutal massacre, the grisly killing, the violent murders &etc., and which picks back up in the happily ever after, when these women, who have suffered these different experiences and have been trying to live out their lives normally, meet up and seem to be targeted again by a mysterious killer. It was a fun read for a while and then it began to annoy and anger me, probably because it shifted from dumb fun to just…stupid foolishness. I’ve never seen a protagonist make so many poor choices in the course of a story! Also it felt like some sort of weird cautionary tale about too much xanax– which, as someone who is too highly strung for xanax to have any effect on…I really just can’t take that seriously.

The Silent Companions by Laura Purcell Haunted, isolated mansions; unreliable, possibly unstable narrators; terrifying works of art that may or may not be possessed by evil spirits; paranoid villagers; secret diaries; creepy children–this book ticked all of my weirdo boxes, and I have to tell you, provided some of the most tense, edge-of-my-seat reading in recent years.

Kabiyo: The Supernatural Cats Of Japan by Zack Davisson. I adored Davisson’s previous book, Yurei: The Japanese Ghost, an exploration of the various ghosts found in Japanese culture, conveyed via warm, relatable anecdotes, deep research, and translations of many centuries’ worth of Japanese ghost stories. It was a pleasure to read, and felt like sitting for coffee with an old friend who had the most wonderful tales to tell. Kabiyo: The Supernatural Cats Of Japan, while just as fascinatingly informative and even more sumptuously illustrated, seemed dry in comparison and lacking in that lovely warmth that so captivated me previously. A worthwhile read for the data and the sublimely absurd imagery, but of the two, I’d recommend Yurei over Kabiyo.

The Terror by Dan Simmons I started watching this nautical horror period piece about a legendary arctic expedition on AMC, and was immediately hooked, but was hesitant to read the actual book because the only other thing I’d read by Dan Simmons–Carrion Comfort–was pretty gross and left a bad taste in my mouth. Also because The Terror is approximately one million pages long. This is not to say I’m intimidated by a hefty tome, but I’ve got stacks and stacks of neglected reading materials, so I’m always a little hesitant to commit to a title whose heft could effectively bludgeon to death a circus strong man. I was additionally a little concerned that I’d be assaulted with all sorts of dry information about ships and sails and jibs and hulls and whatnot, and eh, I don’t need to know all that, do I? Don’t bore me with details! Well, I needn’t have worried; there were loads of details, but somehow they were all fascinating; perhaps because this was a masterfully crafted tale, and each piece of it seemed equally as important as the other. The descriptions of the character’s perceptions of the unknowable geography of the region where they’ve become trapped reminds me of many things that I love about my favorite Algernon Blackwood tales, the terror of being alone and out of your depth in a vast and unknown landscape, how alien, dangerous and even malevolent nature can seem when you’re out in the middle of it and floundering. There is monster in this story, but I feel that it takes a back seat to the monstrous acts of cruelty which emerge amongst members of the crew, and even to the fiendishly brutal terrain itself. Now that I’ve finished the book, I am even more excited to revisit the program and see where it goes.

Little by Edward Carey When Goodreads first recommended this title to me, I thought, “haven’t I already read this book?” But I was getting Little by Edward Carey confused with Little, Big by John Crowley, which I read several years ago and which I enjoyed much more. These stories aren’t terribly similar, though, so maybe you should just read them both and take them on their own merits and then decide for yourself. Little is one of those books that I am glad I didn’t know much about beforehand. It follows the life of young Marie (“Little”, as she comes to be called) a small, pinched and peculiar-looking orphan, who comes to be the ward of an equally odd and eccentric wax maker. The story chronicles their life together in Revolutionary Paris as Marie makes her way through a life that is never easy, and quite frequently pretty awful. Perhaps as soon as you read these sentences, you’ll hone in on a telling detail, and begin to build a picture for yourself of the trajectory of this story and who Marie is meant to be, but somehow–maybe because I am a dummy–it didn’t even dawn on me where things were headed. Reading about characters who can’t ever seem to catch a break is not the sort of story I can comfortably classify as “enjoyable”, and yet, I do think I enjoyed the book overall. (I still think I liked “Little, Big” better though!)

Becoming by Michelle Obama I didn’t finish this title, but not because it wasn’t excellent. This is mainly due to the fact that I was like, number eight hundred on the list at our local library of people waiting for our amazing former FLOTUS’s book, and I was only allotted two weeks to read it. This was a title that I definitely could not return late, as I didn’t want to delay someone else’s enjoyment of it! I’ll be honest with you, I was weepy before I even got all the way through the introduction. Just to know that I was alive and on this planet at the same time as this tremendously strong, beautiful woman and her equally incredible husband, is an extraordinary feeling–and even now it excites and inspires me. I loved this book for the opportunity to learn much, much more about Michelle Obama: her childhood and family life, her college years and early career before she met her husband; her fierce intelligence and her wonderful sense of humor; her compassion and drive to do more and better for her daughters, her community, and the world at large; her strength and resilience, and even her quirks and flaws and shortcomings. She writes in the loveliest, friendliest conversational tone; you almost feel like are are both sharing space in the same room as she is sharing her life story directly with you. I desperately wish that I could have finished the book; I just kept telling myself, “…just make it to the part where Barack Obama becomes President!” and I did. And then I cried some more before sliding it through the library’s after-hours drop-off box.

The King Of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany is one of the five specific books I was designated to read from my 2019 reading challenge. It was a bit of a slog. The kingdom of Erl is lacking in magic. The king sends his son, the prince, to Elfland to procure the Elf King’s daughter as a bride, and to then bring magic into the lands of men. The Prince kidnaps the Princess, marries her, and they produce a son. Despite the fact that he was tasked with finding a mythical, magical wife, and that’s exactly what he got, he soon grows exasperated and embarrassed that his enchanted elfin bride can’t get used to the ways of men, or act normal like all the other boring human peasant-muggles in their backwater little town. The Prince gets huffy and impatient with his wife on several occasions because of her inability to acclimate and in trying to shame and control her, just generally plays the part of the mediocre, privileged, white male that he truly is. The princess, sensing that her husband might be an utter moron who doesn’t actually even know what he wants, leaves both him and their son behind, and runs back home to Elfland and her father. The Prince then spends the rest of the story wandering the countryside, searching for the border to Elfland so that he can get her back. UGH. This was a tiresome story, and it took me 5 years to read it. However, if you can stick it out, the last twenty pages or so are totally worth it, when the awesome witch Ziroonderel tells off a bunch of doddering old farts and marvelous magics starts to creep into the land, whether anyone wants it there or not.

You by Caroline Kepnes When my sister messaged me to share that she was watching a certain show on netflix and she wanted me to watch it as well, so that we could hate all of the horrible characters together…of course I was on board in an instant, as hating awful people with someone you love is one of life’s great bonding experiences. I inhaled it, despite the fact that her request came with trigger warnings and content warnings: it was a show about a psychotic/sociopathic (??) stalker, and she was worried that because of some past issues and trauma I have dealt with, it might not be a great watch for my overall mental health. Which…it was not at all, by any means, healthy for me to watch, but hating on these awful characters was so much fun that it completely trumped caring for my emotional well-being, and I watched it anyway.

(The main character, by the way, is played by Penn Badgley–Dan from Gossip Girl–the setting is somewhere in NYC, and the characters are all frivolous and ridiculous, so the whole time I watched, I just kept expecting smug voiceover narration from Kristen Bell in her Gossip Girl voice, along with extravagant, utterly luxurious brunch spreads.)

I soon realized that this dumb show was based on a book, and so of course, I had to subject myself to even more if it. I read it in the course of an afternoon, and it was equally as trashy and silly as the show. The plot, for me, was a little scary because while it sounds like this stalker is really over the top and goes to a lot of trouble regarding the object of his obsession (hacking her email and social media accounts, breaking into her home, pretending to be someone else online so that he can get information on her from her friends, etc.) and it sounds like these are really outlandish things that are a lot of work, and who has that kind of time, right? No one really does that, right? I’m here to tell you, I know one person who did. And they did it to me. So if you think this is happening to you–don’t worry if you sound crazy or paranoid. People actually do this crazy, fucked-up shit. Sometimes, in my darkest, loneliest moments, I worry that it still may be happening, even now. But…I still devoured this stupid book anyhow. Aside from the fact that sometimes it’s lovely to lose your afternoon to stupid enjoyment, I am at the point in my life where I don’t want to ignore the things that scare me. I know this was a work of fiction, but maybe it’s smarter to know your enemy, than to stick your head under the sand and pretend this stuff doesn’t happen.

Some spooky horror stuff: The Siren And The Specter by Jonathan Janz was a lurid, layered haunted house/ghost story, and that particular flavor of sleazy and deranged reading that used to titillate the heck out of me when I was about eleven years old. I would stock up on the cheap horror paperbacks with the craziest covers from the local used bookstore, stories that aroused feelings of both repulsion and obsession that I’ve never since recaptured until reading this book; Kill Creek by Scott Thomas is another haunted house tale, one in which a handful of modern masters of the horror genre are invited to stay for an evening for some sort of internet publicity stunt, and the usual sort of thing ensues. That’s a really lame review; I don’t actually remember it all that well, but I mention it because I hear Showtime is picking it up, so if you’re into this sort of thing, you may want to give it a read before it airs! I devoured In The House In The Dark Of The Woods by Laird Hunt over the course of an afternoon from a flight back from NYC; this witchy woodland fever dream of a tale, set in colonial New England, is utterly immersive and twisty and strange, and I loved every moment of it. And if you like twisty and strange, When I Arrived At The Castle by Emily Carroll is a deliciously eerie, magnificently illustrated, Gothic horror fairy tale nightmare-poem with the twisty and strange dialed waaay up.

We Sold Our Souls by Grady Hendrix I wish I could have read Grady Hendrix’s We Sold Our Souls when I was 15 and heavy metal was the only thing my weird, lonely heart understood. But time doesn’t work like that, so here I am now, reading a horror-enveloped love-letter to heavy metal music at 42 years of age, and damn if it didn’t throb & thrum my heart in the same thunderous, fearsome ways. I’m a little biased, I suppose. I have loved just about everything Grady Hendrix has ever written; and while know I can always count on him for ridiculous hilarity (even and especially when it comes to horror), what I was not expecting was something so incredibly heartfelt. The story: decades after her rock-n-roll band was on the cusp of their “the big break”, main character Kris Pulaski is barely scraping by, toiling away at her dismal hotel job, and definitely not playing her heart out with the music she loves anymore. What happened that night, that strange distressing night so long ago, when the band was teetering on the brink of greatness? What pervasive evil has insinuated itself into the lives of her former bandmates and is pursuing her to the brink of madness? We Sold Our Souls is a thrilling extravaganza celebrating the enormous power of music, as well as a bleak reckoning with the consequences of “selling out”…and possibly losing your soul in the process.

Meddling Kids by Edward Cantero A tongue-in-cheek horror-comedy mixture of Lovecraftian cosmic horror and Scooby Dooian hijinx, this was a quick, silly read that I couldn’t totally find myself immersed in because I had a real problem with the author’s specific use of similes and metaphors. Which, I KNOW, I can’t pick on someone else’s writing (or editor, I guess) when I am not exactly sure that I even know the difference between the two, but I found the author’s use of wink-wink nudge-nudge pop culture-y type comparisons and analogies awfully irritating and gross, and every time I encountered one it took me just a little bit more out of a story that I might have otherwise enjoyed. Or maybe not, and here’s my second issue with the book. This story is full of references; it’s definitely meant for the horror geek who delights in their knowledge, but whereas the heavy metal mentions and allusions in We Sold Our Souls just felt…right…all this bludgeoning me over the head with teen detective references and genre nostalgia sort of felt like the neckbeardy masturbatory nonsense of Ready Player One. OK–maybe not THAT bad (I really loathed Ready Player One) but it was getting close to that sort of twaddle. And yet, all of my unkind complaints aside, it was sort of a fun story along the lines of “the old team coming together to solve one last mystery!” and all of the twists and turns along the way. So, I guess I don’t …totally…not recommend it?

The People In The Castle: Selected Strange Stories by Joan Aiken –I have been meaning to read this Joan Aiken collection since June of 2016, when I had allotted it, among others, for my summer reading stack. Of course in 2016 I was still catching up on my 2014 reading, so it stands to reason that I’m just now getting around to inhaling this marvelous book of tales. It’s got an intro from Kelly Link, whose brilliant, peculiar writings I love all too well, and if that doesn’t sell you right off the bat, I will tell you that when I read the first story in The People In The Castle, I thought, “ah, so then, this is sort of a cross between Roald Dahl and Leonora Carrington!” In further exploration, however, I found that Aiken’s imaginings are not the sometimes frustratingly surreal flights of fancy that Carrington composed but rather earthier, more practical things. More realistic? No, I would not say that at all, and thank goodness! There are ghost puppies and exotic magics and infernal orchestras galore–but they are experienced by people very much like you and I, living out their lives–people with families, with work situations, people with hopes and dreams, and minute, daily dramas. There’s a subtle but really wonderful humor present in these stories, which prompted the Roald Dahl comparison, but where I think his stories sometimes have awful and unhappy (but kinda funny) things happening to people (and granted, they are sometimes awful and unhappy people) there is a tinge of something sly and dark in his narratives that I don’t find at all in the selections I have read by Aiken. Instead, the tone seems to me one of bright, lively, and benevolence, and coupled with that enchanting thread of dream logic that runs throughout these stories, sometimes glinting brightly, sometimes so faint that it’s but a winking phantom gleam–it is likely these are gentle, magical romps that you could read to children. Except, in several of these vignettes, I will admit, I felt that there was something going on that I didn’t quite understand…something of some importance that lay just beyond my grasp. That, too, is part of their charm, and who better than a child to perceive this and yet still be totally okay with it? Sometimes not everything makes sense. And most times, that’s where the magic lies.

The Vanishing Princess by Jenny Diski After reading this book of delirious interludes I’ve begun to think of Jenny Diski as Joan Aiken’s spiky, sexy, cynical cousin; Diski’s stories are not the gentle, magical romps from Aiken’s magical realist bag of tricks, but rather feel like more adult enchantments, strange pleasures and dreams, denied or deferred, or which at the very least frequently don’t manifest as hoped or planned. Short Dark Oracles by Sara Levine is a wonderfully clever collection of playful, self-aware, and charmingly awkward story/fables. The Only Harmless Great Thing by Brooke Bolander isa heart-wrenching alternative history of devastating rage, radioactivity, and elephant song, is a compact story that is by no means a quick or easily forgotten read. And The Taiga Syndrome by Cristina River Garza follows an ex-detective’s feverish, poetic quest to find a woman who has run away from her husband to the forbidding boreal forests of the taiga, and who may or may not want to be found.

The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter by Margareta Magnusson. Because I am a contrarian (and also because I had zero interest in organizing or de-cluttering) I have been ignoring Marie Kondo and her KonMari madness for years. I like my stuff, thank you very much, and I really have no wish to get rid of it. (“Likes her stuff, and does not like change”– I will give you one guess as to my sun sign!) I recall, though, when this book was released a few years back, I was vaguely intrigued …by the name, at the very least. If I had to choose between the two, which is a tad unfair because I haven’t read the KonMari one, I would point you instead to this 80-something year old woman’s infinitely practical and wonderfully charming thoughts on a sensible way to deal with your possessions as you approach your later years. Less about “sparking joy” than it is, “do I really want my family to have to take care of this shit while they are grieving after my passing?” I related to and internalized her ideas immediately. After having dealt with the deaths of my mother and my grandparents, I have more experience than I would like with cleaning up the messy remnants of someone’s life, while at the same time, having to reconcile myself to the fact that they are no longer around to ask, “hey, what do you want me to do with this stuff?” Knowing what I know know, having gone through that process myself–I would never do that to someone. It’s too much to ask, don’t you think? Read this book. Get your shit together. And then get rid of it.

Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal by Mary Roach. I am super late to the writings and ruminations of Mary Roach and I am cursing myself for wasting so much time. She writes in that murky intersection of the disgusting, the taboo, and the intensely fascinating, and sheds her unique light on what she uncovers there. I’m just going to say it: Mary Roach is the kind of writer I aspire to be, or at least I would, if I wished to put any real effort into my writing and I wasn’t so afraid of failure. Her boundless curiosity, sly humor, shrewd understanding of her subject matter, along with the clever, cunning language she employs in conveying the information she has uprooted, has endeared her to me in a way that I am not certain that any other author ever has. If there is a question to be asked, no matter how weird, or gross, or unthinkable–she is going to dive in and get an answer for it. I have a keen admiration for journalists and writers, who, when interviewing a subject, can simultaneously digest the answers provided by the subjects of their queries, and race to make connections with these responses and from them to extrapolate parallel lines of intriguing query–and in doing so, suss out further explanations and implications and answers that you might not have even expected (or wanted!) For example, from Gulp, a book exploring our bodies’ mechanism of eating, digestion, and elimination, how can you not admire this exchange between Roach and Betty Corson? Corson is a Beano staff member who shared with Roach a few details on the kind of people who called the Beano Hotline– for various problems of a gassy and flatulent nature–and which led to the following exchange:

“Why not just avoid legumes? Some people can’t, said Corson. I challenged her to provide a single instance of a human being forced to eat beans. She came back with “refried-bean tasters.” They exist and they have called the hotline. Can you imagine?”

Refried bean tasters! They exist! Of the numerous tidbits of information contained in this book, like so many pieces of corn that pass through your digestive system to wind up…well…you know where…this bean info is actually one of the least disgusting you’ll learn about, but oh, man. Stick around for the rest of the journey. It’s a wild ride.

I Am Behind You by John Ajvide Lindqvist I am not sure if I should call this horror, or mystery, or what, but I Am Behind You is a surreal, thrilling story that begins on a perplexing and preposterous morning as campers in their caravans awaken to realize, with sinking stomachs and mounting terror, that where they awoke is not quite the same place as where they fell asleep. Packed with uncanny atmosphere, high tension, and characters haunted by more than just their current circumstances, I Am Behind You shows us a place where nightmares are real, events have no explanation, and places no longer exist. What does one do in such a disturbing situation? That’s where the idea gets interesting, while we inhabit each character’s perspective as they struggle with their eerie predicament. If you like a straight-forward, clear-cut ending, you may find this a frustrating read, but apparently this is the first in a trilogy, so perhaps more answers are forthcoming!

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi if you enjoy stories like Pachinko, an epic, sprawling saga about Korean immigrants living in Japan between 1910 and now, then I think it is safe to say you will enjoy Homegoing as well. A breathtaking, emotional, multi-generational tale of a family split between Africa and America, this is a story rich and throbbing with both compassion and misery, and characters who desperately, fiercely live and love in the fleeting glimpses we see of them, in these chapter-long vignettes where time and history, politics, history, and gender interplay. A tale that plays out over many lifetimes and is o doubt is inspired in part, by the question asked by one of the book’s 20th century descendants:

“You must always ask yourself, whose story am I missing? Whose voice was suppressed so that this voice could come forth? Once you have figured that out, you must find that story, too.”

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi Victim or villain? Truth or tall-tale? It is never completely one or the other. “Isn’t life a blend of things that are plausible and others that are hard to believe?” muses Mahmoud, a journalist caught up in a story he cannot reconcile in his wildest imaginings, and yet one in which he is living every day. Frankenstein in Baghdad, a modern, satirical adaptation of Mary Shelley’s gothic classic, is a novel of contradictions and gray areas and what it means to be human (or not-quite-human) living in this contradictory world and navigating these gray, uncertain spaces. One of the book blurbs mentions “the terrible logic of violence and vengeance” and this perfectly encapsulates the unrelenting everyday horrors of a rubble-strewn city in the midst of war, as well as the monstrous creation borne of that violence, now stalking its midnight streets and a exacting brutal revenge.

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan Young George Washington Black, “Wash,” a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation, is taken somewhat under the wing of a new master’s eccentric brother, Christopher. A tragedy occurs, one for which Wash will surely be blamed, and both he and Christopher (or, “Titch”, as his family calls him), escape via Titch’s experimental hot-air balloon contraption. Thus begins a series of world-spanning journeys for a pair whose paths and fates would seem linked at this point, but for Wash, the endeavors are tinged with confusion, desolation, and despair, as he comes to realize that Titch, the only person he has left in this world, would appear to be trying to escape from him. Wash, sometimes doomed and despondent, sometimes emboldened and blazing with spirit, continues to endure, to strive, to propel himself forward–whether as part of forging a future life for himself, or to find Titch again, and demand the answers that plague him, from the past that shaped and formed him–maybe both. I couldn’t put this book down. It was agonizingly beautiful and soul-crushing and exhilarating. It was exhausting. I can’t recommend it enough.

Giant Days Volume 9 If you’re not already reading about the university adventures of chums Esther, Susan, and Daisy, then I envy you immensely the experience of discovering these delightful characters and their adventures as they navigate friendship and love and responsibility, while trying to pass their college courses, find housing and jobs, and figure how who they are and what they want their lives to be.

It’s difficult for me to talk about Giant Days without getting all choked up and emotional–these characters are the labor of love of John Allison, the artist who created Scary Go Round, the first web comic I was to ever discover, back in 2003 or so, and whose works as they grew and changed and evolved, are actually only web comics I still read. Described as “postmodern Brit horror”, Scary Go Round follows the hapless denizens of Tackleford, a fictional British town beset by all manner of supernatural activity including, but not limited to: zombies, space owls, the devil, and portals to other dimensions. Though Scary Go Round ended in 2009 [note: it periodically picks back up again!] a few of Allison’s beloved characters moved on to Bad Machinery, which picks up in Tackleford 3 years later. The focus is on an entirely new cast of sleuthing schoolchildren attending Griswald’s Grammar School, whose well-intentioned energies may cause more problems than the mysteries they solve – but they throw themselves into it all with much vigor and aplomb.

It is from these stories that Esther, Susan, and Daisy emerge, and I am only telling you all of this because you have so much to look forward to reading, between the ongoing Giant Days series, and the previous two web comics! Marked by clever, peculiar dialogue, absurdist humor, dotty characters (and delightful fashions), Giant Days is so much fun, and I want you to come back to me right here and tell me how much you love it, after you get started.

Re-reading some haunted house books! The Haunting Of Hill House by Shirley Jackson was an imperative re-read and a palette cleanser after my experience with the Netflix series. I did not love the show for many reasons but most of which because all of Jackson’s elegant, powerful symbolism was reduced to “easter egg” status. I won’t spoil it for anyone who loved it, or who hasn’t yet seen it, so that’s enough of that. And if I am going to read of Hill House, then of course I must re-read Richard Matheson’s pulpy, lurid Hell House for comparison.

At first glance, they are somewhat similar–a small group of people, mostly strangers to each other, congregate for research purposes in houses known for their haunted histories. But Jackson and Matheson’s treatments of this spooky trope are so very different, and I really urge you to read them side by side for the differences in tone and language, the whos and whys of the characters and how they interact and relate to each other (or not), and to see how each story evolves and diverges. Interesting to note, if you are not already aware: Richard Matheson is also the author of I Am Legend, What Dreams May Come, A Stir Of Echoes, and the Twilight Zone episode “Nightmare At 20,000 Feet”.

666 by Jay Anson and The Manse by Lisa Cantrell were two used finds that I picked up while visiting Phantasm Comics in New Hope, PA. Lured in by their ridiculous covers, I devoured both on the flight home; In 666, our main characters, a married couple, arrive home from vacation to find that a new house has somewhat mysteriously appeared more or less across the street from their own home. We learn from vague visions and various forays into the house that this structure is evil because it was built from various pieces of diabolical or horrific materials throughout history? (i.e. pieces of torture devices, stones from notorious dungeous, nails from the cross Jesus was all got up on, etc.) I’m probably oversimplifying, and this is already a dumb book to begin with. Anyway, this house reappears and disappears over the years after inciting its inhabitants to dreadful violence. Somehow the devil is involved. The devil is a realtor? Or a house flipper? I don’t know. One amazon reviewer enthuses, “Every christian should read this book”. OKAY THEN!

In The Manse, some self-important small town JCs (junior chamber of commerce members) decorate a local historical space–an old house owned by two doddering spinsters tucked away in a local ALF– every year for Halloween and make enough money from their haunted house doings to keep the old place afloat for another year. But! The house is apparently situated over a portal to hell and feeds on the fear generated by these annual Halloween shenanigans, and by its 13th year, its saved enough fear-bucks to do something big. But…what exactly? I am not sure. Hell’s grand opening, with lots of samples, like a Saturday afternoon at Costco, maybe? I feel like these vintage paperbacks are always sketchy on the details of whatever the titular Big Bad is actually trying to accomplish. The Manse, much like 666, is awfully silly, but the cover art of a demonic jack-o-lantern intensely nomming on a cobwebby banister is actually pretty great.

Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval Norwegian multidisciplinary artist Jenny Hval has written a surreal debut novel full of gross words that you may have issues with if you can’t handle moist ooze, bubbles of spit, sticky crotches, or other goo-soaked situations or similes. If you’re all good with mucus, rot and pus, blood, spores, and urine, well, then. You’re in for a treat. In Paradise Rot we follow Jo, an overseas student studying in a foreign country, anxious and adrift in her new surroundings. After a week’s worth of fruitless and frustrating searching for housing, she answers an ad for a roommate for what we find out is actually a converted warehouse with a strange inhabitant, who has been living there alone. “In a house with no walls, shared with a woman who has no boundaries,” Jo experiences a soporific, psychedelic sexual awakening as her surroundings decay and fall apart around her.

Hungry Ghosts by Anthony Bourdain I, sadly, became more a fan of Anthony Bourdain posthumously, and it really began, if I am being honest, when I learned that he had cooked up this illustrated collection of eerie food tales steeped in Japanese folklore and legend. The book opens with the story of a Russian oligarch who, in the middle of his dinner party, invites the chefs working in his kitchen to play a version of 100 candles, or Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, a Japanese Edo-period parlour game in which brave samurai would try to one-up each other with terrifying tales of ghosts, demons, and unspeakable beings. In this version, however, it is the chefs who share these dark and gruesome tales about food and hunger, with each story taking inspiration from the many horrors found in Japanese mythology. “ Generally speaking, I always want more from these types of anthologies than they are able to deliver, but this one was a lot of fun, and more successful than most. Recommended if you liked Zac Davisson’s Yurei: The Japanese Ghost.

Junji Ito’s Frankenstein I’m not sure how much I really need to try and sell you on this one. If you like Junji Ito, then you know you need his grotesquely illustrated Frankenstein for your collection. And if you dig Mary Shelly’s gothic classic, Frankenstein, then you probably want to see this bizarre Japanese illustrator’s take on the beloved tale. Bonus: Frankenstein only takes up half of this hefty tome–the other half features the many misadventures of Oshikiri, a high school student who lives in a decaying mansion connected to a haunted, parallel world. Oh, you’ve not heard of my favorite illustrator, Junji Ito? Have a read of “The Enigma of Amigara Fault“, a story which I think is pretty representative of the tales he likes to tPostell, rife with themes of body horror, obsession, helplessness, and mystery– and I guarantee you’ll be able to gauge for yourself right away if his work is something you’ll enjoy. Also, Junji Ito, can you pretty please illustrate an edition of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray ? I haven’t read it yet, and yours is the version with which I wish to initiate myself! (Don’t give me a hard time! I’ll read it one day! It’s on the list.)

Bad Gateway by Simon Hanselmann Ooooof. When you strip away the spiteful laughter and the uncomfortable chuckles of the previous Megg & Mogg books (one of which, Megahex, I have written about previously–don’t get me wrong, I adored it, and I laughed at that one, too) you’re left with the bare bones of depression and mental illness and addiction and self-harm and a bleak, unblinking gaze at your trauma and terrible behaviors. Where do you go once you’ve hit the bottom of the bottom? If anyone could fall further, it’s this gang, and yet, I am hopeful that is not the case. CW: everything.

A Hawk In The Woods by Carrie Laben Recommended as a “best of 2019….so far” by Jack over at Bad Books For Bad People, A Hawk In The Woods was described as a “Lovecraftian sister road trip,” and OK, yes please–sign me up! Abby and Martha are twins from a weird family with weird powers and are desperately headed to the family cabin after Abby breaks Martha out of prison. Are Abby’s reasons for rescuing her sister entirely unselfish? Absolutely not. As we follow the trajectory of their journey, the timelines slips from past to present and we get a glimpse of the reasons they each wound up where they did in life, and where that path will ultimately lead them. There was so much about this story to love: the sister’s relationship, the creepy family backstory, the powers that the twins possess (Abby uses people’s energies to bend those individuals to her will, and Martha can fold time) and the only complaint I have sort of spoils an important aspect of the story, so I’ll keep mum on that point. Just…pay attention to who the characters are, and what you think you know about them. Things can get a little confusing.

The Poison Thread by Laura Purcell. I won this book in a GoodReads giveaway! I swear I get emails from GoodReads every other day about how this, that, or the other book on my to-read list is now available and they are giving away 50 copies of it, or something like that. And honestly, you won’t catch me entering a lot of random internet giveaways, but it just seems like sooner or later between the frequency of them and the amount of stuff they give away, you are going to win something from GoodReads– so why not? Seriously, just enter them every chance you get; you’re bound to luck out at some point. The Poison Thread (aka The Corset; I am not sure why they changed the title) is the second book I have read by Laura Purcell and I was so very excited about it because I thoroughly enjoyed the first I’d read by her, The Silent Companions, a book which genuinely freaked me out . In The Poison Thread, the narrative is split between two women in Victorian England; Dorothea, a wealthy heiress, and Ruth, an impoverished seamstress imprisoned for the murder of her mistress. After the death of her mother, who contracted a bit of religious mania before her slightly suspect passing, Dorothea, or “Dotty” begins visiting women in prison, among other acts of charity– and I’m not quite sure if it’s to honor her late mother’s legacy or an excuse to practice her newfound fascination with phrenology. This seems an odd, throwaway theme in the greater scheme of this tale–I think you could swap in and substitute any faddish psychoanalytical nonsense from the era and it probably would not have made much difference to the story. Dotty becomes singularly obsessed with Ruth, who believes she has killed via transference of her malice and rage through the power of needlework. This is perhaps more “gothic suspense” than “gothic ghost story”, although that thread of the supernatural does lurk throughout, even it if may only be in Ruth’s mind. But it’s an utterly riveting and twisty novel and I’ve been recommending it to everyone I know. If you’ve read neither The Silent Companions nor The Poison Thread, grab them both as we head into September and I assure you that they will make incredible early autumn reads.

The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang is a book that I started earlier in the spring and finished in May and I’m still not certain how to even begin to tackle the material. I feel funny saying that I “enjoyed” a book that personally chronicles a woman’s exhausting experience with psychosis and a perpetually shifting reality, but in truth, I did tremendously enjoy it. Or, rather, it feels more human to say I enjoyed learning more about what it is to live with schizophrenia, a diagnosis that has always both intrigued and terrified me in equal measure, I suppose, because of the streak of mental illness that runs through my own family. Intimate, candid, and immediately compelling, these vivid, tangled essays provided perspectives into both chronic and mental illness and insights that were surprising, terrifying, but also wonderfully illuminating, sometimes even quite empowering.

I spent two weeks in the psych ward immediately following a suicide attempt when I was 28 years old; my memories of that time are a collection of amorphous moments of cloudy despair alternating with slices of razor-sharp fury and crystalline focus. I was not experiencing a psychotic break; I wasn’t hallucinating, my reality wasn’t (exactly) fracturing–my experience was not even close to that of the author’s, but I wasn’t myself while I was there. I had a very hard time finding my way back. In the course of these writings, the author shared some things that helped her when she felt herself starting to slip, and I feel that had I access to such ideas, they might also have helped me. When she starts to feel the onset of what she describes as a sort of psychic detachment, “episodes that preclude psychosis, or even mild psychosis–the episodes in which I must tread carefully to keep myself where I am,” she implements small, symbolic systems of defense or spiritual safeguards that have a connection to the “sacred arts”. The solace granted by these practices is not through the beliefs accompanying them, but rather the actions they recommend. “To say this prayer–burn this candle–perform this ritual–create this salt or honey jar–is to have something to do when it seems nothing can be done.” If the delusions come to call, she has a ribbon she will tie around her ankle: “If I must live with a slippery mind,” she muses as the last essay concludes, “I want to know how to tether it, too.”

The Word Pretty by Elisa Gabbert. I like books in which people spend time thinking about things; especially when it’s the writers themselves thinking about things, and even more so when those things being pondered are related to their craft. They are the kinds of conversations and connections and observations that I’d like to share with people, if I weren’t so self-conscious about sharing (or having an opinion or talking to people at all…) and so instead I read about these internal conversations in the form of brilliantly inquisitive and obsessive essays, written by other people. Even on the subjects and anecdotes I related to or connected with, though, it was on the level, I felt, of a lower life form. Elisa Gabbert writes like the accomplished, sophisticated interesting-in-all-ways person that I wish I was, and I felt like I was an amoeba trying to relate to some sort of higher being, complete with halo and wings. Even if I thought I was relating exactly to a particular thought, was I really? Would I even know, middling mediocre hack that I am? The more I read, the more unsure of myself I grew…and yet, I could not stop reading. Elisa Gabbert, I am sure that you are a very nice person and it was not your intent that I feel this way. I loved this book, even though I did not love the way I felt about myself when I read it.

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin is apparently “far too bewildering” for one reviewer on Amazon and if that’s not your thing, then you may want to skip this slim book of surreal, unsettling stories. To be fair to the stories, though, I think this reviewer might have had a very low tolerance for the bizarre. There are no happy endings (and very few happy beginnings or middles) and really, several stories don’t even quite have a proper ending, happy or otherwise– rather just an abrupt stopping point or a vague notion that the story may continue forever, whether or not we are still present and reading. Many of the tales are dark and violent, brutal and heartbreaking, but the one I loved was not particularly shocking or tragic. It involved the theme of familial bonds: one adult brother’s bemused and at times perplexed recounting of another brother’s depression, in the midst of a family that seems to be thriving and in which everyone else appears to be hunky-dory. I don’t think I’m remembering it exactly as I read it, but at one point, in a brief and sudden flash, the successful brother, at a family barbecue full of mirth and merriment, experiences an unexpected moment of (was it sadness? anxiety? maybe more of a nothingness? A nothingness that might last forever? I can’t recall) but I remember feeling… vindicated, and a bit vindictive, when my first thought was “so then…now you know how it feels.” I’m neither a masterful enough reader nor writer to say if that was a bit of subtlety on the part of the author, or if she aggressively smacked us over the head with the notion, but I felt what I felt, and I loved that profound punctuation in what was otherwise one of the more reserved, not particularly ambitious feeling stories in the collection. It elevated it somehow, to something extraordinary.

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan. Sometimes I like to read trashy books. And when there are obscenely rich people in the story, spending their money in stupidly extravagant ways, that is the maybe best kind of trash. It’s particularly good for in-flight reading. I usually leave these books in the lodgings I stayed at, for someone else’s trashy enjoyment. You can find my copy of Crazy Rich Asians in the bar of The Rosemary hotel in L.A.

Mongrels by Stephen Graham Jones I first read Stephen Graham Jones (Mapping The Interior) in September of 2017–again, during a hurricane! It’s become a bit of a tradition, I guess. I was under the impression at the time that he was a new author and that was his debut novel, but I couldn’t have been more wrong; he’s a very prolific writer and has been at it for quite a while now. Mongrels is a surreal werewolf coming-of-age tale; it’s violent and beautiful and brimming with odd moments of absurdity and heartbreaking tenderness and tragedy. It is one of my top ten…no, make that one of my top five favorite books of all time.

In The Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado. In seeing initial reviews about the brilliant structuring of this vulnerable, spellbinding memoir of abuse, I grew wary, worrying that it might in some way be above my intellectual paygrade. And though it is framed through the analysis of popular horror tropes and footnoted with scholarly snippets regarding folk & fairytale motifs, I needn’t have worried–trauma transcends literary conventions.

I read In The Dream House compulsively; that is to say I dreaded every single word of it, but I inhaled them heedlessly and headlong, not unlike watching a scary movie through the shadowed, in-between slants of our joined fingers as we hold our trembling hands before our eyes. In the story of someone else’s hindsight we re-experience our own humiliations and hurts, our own abuse and trauma, and that too I dreaded. But I craved it, as well. Sometimes I doubt what happened to me, and I seek out these types of memoirs. I want to see my trauma appear large as life in someone else’s story. In a painful grip, or a hateful word, a whispered threat. An unwanted touch, a violation of self that transcends the physical act to such an extent that you almost feel you need to scrub your very soul of it.

I don’t want these things to have happened to someone else. Never ever, not in a million years. But when confronted with someone else’s story, I encounter mine, and I am glad that I am not alone. I don’t want to look. I can’t look away. In the Dream House is a book you dare not look away from.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa. Is it possible to both fall in love with a book and want to pretend that you never read it? That it had never been written? That the idea never even existed in the author’s mind? That line of thought is somewhat in keeping, I suppose, with the premise of this quiet, surrealist dystopian drama: on an unnamed island, things and objects are disappearing. The characters wake up one day, and, for example, fruit has disappeared. I don’t think the fruit literally disappears, but rather the idea of fruit. When a disappearance happens, and the villagers become aware of it, they just take all the fruit and dump it in the river. By the end of the day, fruit has ceased to be, even in their memory. The Memory Police ceaselessly monitor the inhabitants of the island and ensure that what has disappeared remains forgotten.

A feeling of dread is pervasive throughout the entirety of the novel, and yet it never seems tense–the islanders seem resigned to the disappearances in a frustratingly apathetic, good-natured, “oh well!” sort of way. There are those among them, though, who don’t forget. It is through their dismay and anxiety regarding the disappearances (what happens when, say, body parts start disappearing?) and fear of the Memory Police (who arrest non-compliant citizens in the middle of the night, and no one knows what happens to these friends and neighbors) that we experience these concerns. We can’t rely on the protagonist for this–she’s too passive for reflection or much in the way of active resistance, even as her career is brought to a close by the disappearance of books (she was a novelist), even as her own limbs begin to disappear. The Memory Police presents such an upsetting concept that I cannot contemplate it overlong. Not that of state control–which ok, that’s pretty bad, I get that– but of the absence of memory. Words like “terrifying”, or “haunting”, or “sad”, just don’t cut it. This book is upsetting. I wish I hadn’t read it. But oh my god, how glad I am that I can’t forget it.

Frankisstein by Jeanette Winterson was a wildly inventive, wonderfully clever, deeply philosophical gem that I am going to be pondering for a very long time, and though it’s a few weeks too early to make any “best-of” declarations (and I’ve got loads more reading to do before December 31st) I think it is safe to say that Frankisstein is going to be near the top of that list. The parallel, temporally fluid stories of both Mary Shelley, dreaming up and penning the tale of her infamous monster, and Ry, a young transgender doctor in modern Britain, who meets and falls in love with Victor Stein, a professor and professional TED talker on the future of AI–and I’ll say no more. I think this is a book you best dive into knowing little, forming your own musings and reflections. I will add, though, this: at some point in the story, Victor softly asks of Ry “…have we met before?” And with that, I experienced the most spendidly delicious shiver, the echoes of which I can still feel when I think on it now.

Body Horror: Capitalism, Fear, Misogyny, Jokes by Anne Elizabeth Moore. It sounds a little childish to call someone a “great thinker” (I used to call my grandmother a “good cooker,” for example. When I was five. ) but these essays on the “gore of contemporary American culture and politics” in relation to the female experience are surely written by someone of capable great–no, make that brilliant–thought. She draws fascinating parallels and somehow ends up connecting concepts such as Standard Time and the time that the unwell need as opposed to the healthy; the choice not to bear children, the cultural imperative to reproduce, and the gendered imbalance of intellectual property rights, and the plight of Cambodian garment workers, a heartrending piece of writing that requires no connection to anything else at all.

I loved how Moore’s writing lends to meandering ruminations–nothing so difficult to follow as “stream of consciousness,” but there’s also nothing at all resembling a rigid structure framing these words. They’re more a disciplined ramble, perhaps with some surprising jumps that she makes in terms of logic and connections, but they are not in the least unbelievable. Moore is an excellent guide through her thoughts, disparate as they may appear at first, and you can see how to got to where she went with each topic. Body Horror was full of uncomfortable, painful ideas and truths, but was it was also powerfully edifying and felt vital and fierce.

Ration by Cody T Luff Full disclosure: Ration was sent to me as a review copy. I don’t regularly receive review copies of things, but I love that someone came across a story or an author that I might be into and was keen to send it my way. That level of thoughtfulness in these kinds of sometimes rote-feeling PR endeavors means a great deal to me, and so one might be forgiven for being under the impression that because of this I was predisposed to think highly of the book, but truly–I had no expectations! Expectations or no, I was incredibly impressed. Described as a “women-led Dystopian piece about surviving in a hunger-regulated society” Ration was a tense, gut-twistingly visceral tale that was heavy and harrowing, and emotionally difficult to read (in the way that The Handmaid’s Tale is heavy and hard to read) but at the same time, thoroughly compelling. I could imagine Ration as a gripping miniseries–the characters and their interactions really were that wonderfully and terribly, vivid–and I could have spent a great deal more time in their bleak, ravaged world. I look forward to reading more by Cody T. Luff and I expect that Ration is going to be on several “best of” lists for the year. It certainly will be on mine.

Fake Like Me by Barbara Bourland A thriller set in the art world and a “love letter to the labour of artmaking,” Fake Like Me was a fantastic read that I tore through in one day and a story that hit so many of my sweet spots. I am a super boring person with a 9-5(ish) job because I crave security and stability and routine–but I am intensely fascinated with artistic creatives who live bohemian, unconventional, vagabond lifestyles. I would like to do this! But I am shy and squirrelly and don’t want to have crazy artist parties and I also like a steady income! Fake Like Me combines a thrillingly immersive examination of the lives and deaths of a handful of intertwined fictional artists, along with something that Sonya has mentioned before here in Stacked at Haute Macabre–their preferred genre of books is “non-fictiony fiction,” where the author “went down some kind of research hole that utterly fascinated them but, because they are a fiction writer and not, say, a journalist, turned their up-all-night discoveries into a story.” If any of this sounds like a good time to you, I think you’re going to love the arty insights and perspectives found in Fake Like Me. Also, don’t be put off by the name, which makes it sounds like it’s going to be a really fluffy read. It’s not.

Dead Astronauts by Jeff VanderMeer was a fractured, fragmented, timeshifting story of dissolving, surreal, decidedly-non-linear layers that I hesitate to even call a “story”. If you are familiar with VanderMeer’s writing, up the strangeness and beauty and WTF factors by ten or twenty or one hundred, and that’s Dead Astronauts for you. It was brutal and heart-rending and utterly confounding, and it eluded me at every turn. At no point did I get a clear sense of what was happening to whom or how or where or why, But. I also left every page that I turned damp with my tears. Something inside me understood something about these allies and their journey and their pain, and when it ended, I wept quietly for a few minutes, thinking, “but…I didn’t want this to end.”

Stephen King Project update: I have read The Dead Zone by Stephen King, which, if I am being honest, I had actually thought it was a collection of short stories before I checked it out of the library. A guy gets a few head injuries, goes into a four-year coma, and wakes up with premonitory psychic abilities. This book felt like old-school Stephen King to me, because I guess it is super old Stephen King thoughts and insights and stories. When I contrast it against something like The Outsider, which is much more recent, well…The Outsider feels like it was written for television. Some sort of essential Stephen King weirdness just…isn’t there. I am almost tempted to say there’s something simplistic and Dean Koontzian about it (sorry Dean Koontz fans, I am not amongst your ranks.) I don’t want to say it feels “dumbed down” because I don’t know that I’d ever considered Stephen King’s writing particularly nuanced! I mean…nuance and complexity… that’s not why we all fell in love with him when we were eleven years old, right? I don’t know if it’s the stories themselves, or the way the stories are told, but there was something missing for me. I’d love to hear some of your thoughts on this, my fellow Stephen King fan-friends. If you haven’t read The Outsider, maybe take a pass and watch the series instead, which is moodier, gloomier, more beguiling and much better than it has any right to be. Oh, and I also read Gwendy’s Button Box which I think was kind of fun and probably way more appropriate eleven-year-old-us, even though we wouldn’t have appreciated why until we became the old farts we are now.