2023

In a recent interview with Jessica Chobot of the Bizarre States: Resurrected podcast, I was asked questions about art that might not make it into my books, and why, and I thought I might share that snippet of Q&A here today. It seemed an appropriate segue for a new blog post featuring a whole slew of artworks that I included in earlier drafts of my most recent book, The Art of Fantasy: A Visual Sourcebook Of All That Is Unreal but which never made it into the final pages. There’s practically a whole separate book of works here!

For each work here today, I have included the initial caption I had written for it. These are mostly unedited, because at some point in the process it was determined I was unable to use them, so there was no point in further tweaking what I had written. I know a lot A LOT of folks who have purchased my book or read a review copy (thank you!) are probably thinking, “why is there no Frazetta or Froud in this book?!” and man oh man, I wish there could have been. They were on my wishlist from the very beginning. Brian Froud (above) and Frank Frazetta (below) were in my original drafts but had no accompanying captions because I had hoped to include them in as full-page intro artworks in one chapter or another, and those images didn’t typically include extensive captions. But sadly, we could not acquire those permissions.

You will note the works featured below are almost all exclusively by contemporary artists. There were some older works that did not make the cut, but honestly, those artists are long gone and don’t really need the exposure or the support, so that is a round-up for another time!

**Bonus material!!** If you’re curious about my inspirations, wishes, and dreams in terms of fantastical art, here’s my Pinterest board of ideas!)

Jessica Chobot: For each of the books (Occult/ Darkness & Fantasy) how do you decide what artwork and artists get included and which do not? What’s the process in making the cut?

S. Elizabeth: This is something that happens from almost the very beginning of the process straight up through the end. I’ve worked with the same editor for all three of my books, and from a procedural standpoint, the projects are pretty similar. The first step is to assemble a sort of dream list of artists or artworks I want to include. My editor will go over it and give some feedback, and mostly I’d say it’s 70% “Sure, these are great,” and 30% “No, I don’t think so, it’s too this, that, or the other thing, or not enough of this thing we’re trying to convey.”

From then, I’ll study the works and see what themes jump out at me and what other works share those themes and come up with a sort of structure that connects everything. To me, that’s a little more interesting than a book of art that groups things chronologically or by art movement or some such. At this point, we’ll schedule a series of deadlines where I’ll submit, say, three chapters for review. In review, it’s again possible that my editor might say, “okay, these three artists don’t really fit this theme very well, can you find more appropriate examples?” And so on and so on until I’ve written the whole book. At that point, there might be 50-100 artists who didn’t make the cut!

And then, once we’re all satisfied with everything…we have to reach out and acquire permissions from the artists. Sometimes, it’s pretty straightforward, and that’s great, but sometimes you have to go through an agent or a gallery or an estate if the artist is deceased; sometimes the artist’s fees might be too much, sometimes there’s no way to get ahold of the artist (so many contemporary artists do not have clear-cut ways of contacting them!) and even if you have jumped through a thousand hoops to find a way to email or DM them…they might never respond. Or they might say no! Which while disappointing, is totally fine and understandable, and that is not a complaint on my part. No artist is obligated to do anything with their work once they’ve created it; they don’t have to sell it, license it, or even show it if they don’t want to! So, at this point, I might have to cut another 50 pieces from the book and work on finding 50 new ones! Sometimes there are even issues with the public domain artworks that I’m trying to include, so even these types of works are not a 100% sure thing. Putting together image-heavy art books is A PROCESS.

JC: What’s an example of something that you wish you could have put into one of the collections? Is there something that hit the cutting room floor that, in hindsight, you think maybe should have been left back in?

SE: In The Art of the Occult, I wish I could have included Rosaleen Norton, the infamous Witch of King’s Cross, whose works were bold and beautifully perverse, and hers were some of the very first I thought of in compiling my initial ideas. In The Art of Darkness, I would have loved to include Gertrude Abercrombie’s stark, witchy, enigmatic landscapes and portraits, and in The Art of Fantasy, OF COURSE, I was desperate to include Brian Froud because in a book of fantasy art, how could you not? But it’s not always meant to be, and in the end, I am over the moon thrilled with all of the artworks and artists that we were able to include and who permitted us to use their work. What’s a little irksome is that there will be readers who are like, “I can’t believe that X/Y/Z artist isn’t in here!” And it’s like, “I’m sorry, dudes! I wanted them in there, too!”

Anyhow, so there’s that! See below for a gallery of fantastical art-shaped holes in my heart (and book), as well as some notes/thoughts on each.

Untitled, Yoshioka

This enigmatic mistress of owls was for a time one of those frustrating internet mysteries of the modern age wherein one’s friends or acquaintances or even a stranger’s social media account shares imagery but they don’t know who the artist is or where it came from. Luckily for us, we also live in a time that provides us tools and technology to help us find the answers to questions like this! Not much is known regarding the elusive creator responsible for this work, known only as Yoshioka but we can let our imaginations run wild envisioning the owlish tea-party fantasy magics steeping in this hazy scene.

Morningstar, Lily Seika Jones.

Lily Seika Jones is a full-time artist/illustrator whose highly detailed, whimsical watercolour and ink paintings, take inspiration from her favourite childhood stories and mid-century illustrators, as well as the natural world of the Pacific Northwest. Lily is interested in how myths and fairy tales shape our childhood and the world around us, and sees her art-making as an exploration of the significance of these stories as we grow up.

Untitled, Rachel Suggs.

Rachel Suggs’ brilliantly imaginative work combines inspired colour palettes and tender sensibilities with fanciful flora and fauna for scenes that feel like you’ve had a brush with a fantastical daydream. In the folklore of various cultures and ancient civilizations, rabbits have been known to represent a kind of Trickster figure. In Chinese, Japanese, and Korean mythology, rabbits live on the moon. These bunnies and assorted rabbit-like creatures have hopped down through many years of history into our fantasy stories!

Beauty, Susan Seddon Boulet

Captivated in early childhood with nature, the freedom of animals, and the magic of the moon, Susan Seddon Boulet (1941 – 1997) enjoyed a rich fantasy life on the cattle ranch where she group up and through the folk tales and stories told by her father and caretakers on the farm developed her love of fantasy and fairy tales. Sent to Switzerland once she displayed a talent for drawing, Boulet went on to create over 2000 pieces of art over the course of her life. Influenced by a variety of writers and philosophies, including Ursula Le Guin, and Anais Nin, as well as Jungian psychology,, the Tarot, the I Ching, this artist mined the collective psyches of unseen worlds for the rich vein of wonder and reverie that suffuses her numinous works.

The Witch King, Anato Finnstark

Seekers on a sacred quest to experience epic amounts of the mythical and magical in their art will rejoice in the realms of mystery and wonder wrought by fantasy artist Anato Finnstark. A freelance illustrator based in Paris, in the dark shadows of this thrillingly frightful creation, Finnstark brings us an undying sorcerer of incomparable fear and dread, the Witch King of Angmar. Once a mortal king of men, the Witch King was corrupted by one of the nine Rings of Power, becoming an undying wraith in the service of Sauron from J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy stories.

The Horus Heresy, Adrian Smith

I have it on good authority that It may be impossible to sum up Warhammer 40k in two sentences. I’m going to try. A miniature science fantasy tabletop wargame that takes place in the grim darkness of the far future where there is only war; a dystopian vision of the 41st millennium replete with a xenophobic and fascist galaxy-spanning Imperium of Man, fighting innumerable neverending conflicts against various inhuman opponents, among them sadistic space elves, raging interstellar orc hordes, and, of course, their own traitorous comrades. An amalgamation of every science fiction subgenre, trope, plot, etc., all cranked up to 12– it’s a lot and to sum up, the Warhammer 40K universe is a pretty horrible place to live. Adrian Smith is a British illustrator especially well known for his work depicting the darkly horrific fantasy worlds in the early days of Warhammer and 40k.

Goblin, Itsuko Azuma 1984

To say that Japanese artist Itsuko Azuma is a bit of an enigma, or a mite elusive–well, that’s certainly a massive understatement. There is not much in the way of information available on this creator, so let us instead examine this creature that they have conjured onto the page. Goblins, or some form of goblin-like creature, are found in cultures the world over, and typically their small stature belies the vast unpleasantness of their disposition. Ill-tempered and gleefully malicious they are! This example, in Azuma’s distinctive dreamlike and trembling style, portrays a little goblin person dancing a furious jig atop a mushroom.

American artist Jeffrey Catherine Jones’ (1944-2011) beautifully haunting images graced the covers of over 150 books through 1976, and fantasy artist Frank Frazetta called Jones “the greatest living painter.”* Jones’ visions of gently contemplative women, awash in atmospheres of solitude and brooding elegance engaged fantasy enthusiasts in a different way, creating a quieter, more reflective, and emotional connection to the art than the era’s more commonly depicted oiled and gleaming muscle-bound, sword-swinging counterparts .

Michael Wm Kaluta

An admirer of Aubrey Beardsley, and Alfonse Mucha, and later Roy Krenkel and Frank Frazetta, these influences can be glimpsed in the work of Michael William Kaluta —and yet the exquisitely elaborate detail depicted in his visions is intensely, unmistakably his own. In the mid-1970s, this artist rented a studio with three other dreamers of fantastical brillance: Jeffrey Jones, Bernie Wrightson, and Barry Windsor-Smith, (some of the names of which may sound familiar because you read about them earlier in this chapter!) Together they formed an artists’ collective, known simply as The Studio, an association lasted which lasted only four years, but an enduring impact on these artists’ works. Known and praised for his Lord of the Rings paintings amongst many other things, Kaulta also contributed artwork to Glenn Danzig’s fourth album, Black Aria. You wouldn’t think I’d try to work a Glenn Danzig reference into a book celebrating the beauty and majesty of fantasy art but I have no shame and here we are.

untitled, MON

I have been losing myself in the lush, lepidopteran shadows of this suit of armor ever since I first espied it. Or is this not a protective carapace but rather a tender cocoon of fragile, filigreed chaos, color, and poetry? Whatever is happening here, this glittering, Baroque haiku of a creature by Japanese artist Mon Mon (b.?) has thoroughly captured my imagination and I am desperate to know their story, how it unfolds and unfurls, and where its glittering mystery ultimately leads us.

Sibyl, Barry Windsor Smith

Whether you reveled in the beauty he brought to the barbarian, Conan, were enchanted by the romance of his dreamy fantasy paintings, or perhaps you were bewitched by the inclusion of one of his most eerie works in my previous book, The Art of the Occult, no doubt Barry Windsor Smith’s art left a lasting impression on your psyche and your heart. Heavily influenced by the art of the Pre-Raphaelites and Art Nouveau, with a fluid penwork and hatching style reminiscent of illustrators of Arthurian legends like Howard Pyle, this Eisner Award Hall-of-Famer, genre-shaping fantasy artist and 50-year veteran of the industry is noted as being the first bring those sensibilities to American comic book art in a significant way.

“Transfiguration” from The Moon Has Come Up, Sulamith Wulfing

Born in 1901 to Theosophist parents, German artist and illustrator Sulamith Wülfing (1901-1989) began drawing her visions of angels and nature spirits at age four. These enigmatic visions continued throughout her life and directly inspired the delicate otherworldliness of her wistful twilight paintings that we still swoon and sigh over today. Wülfing paintings typically conjure a fairy-tale atmosphere, featuring fair-haired, fey young beings in luminous woodland settings, surrounded by brambles and thorns, moths and butterflies, and delicately rendered florals.

Beholder, Scott M. Fischer, Forgotten Realms Monster Manual

Scott M. Fischer. (b.) is an old-school D&D player who loves fantasy art and who has been creating the sort of art he loves for Wizards of the Coast iconic Magic the Gathering game, among other things, since the mid 1990’s. As a matter of fact, in the 4th grade, he had a school assignment about what he wanted to be when he grew up, and he recalls writing “I want to make the art for Dungeons and Dragons.” We must imagine then, having the dream-come-true opportunity to illustrate the Beholder for the Monster Manual, his inner fourth grader must have been over the moon! What’s a Beholder, you ask? Well, I am glad you did, though you may not be glad for the knowledge. A beholder is all head, with a slavering set of jaws, and has ten eyestalks and one central eye, each manifesting nightmarish, deadly magic. Floating through the air, carving out their lairs with their eyebeams, these despotic monsters are terrifically paranoid, megalomaniacal delights.

Thomas Blackshear

African American artist Thomas Richman Blackshear II works are things of wonderment: blessings and lessons. Strange miracles. Heavens and hells. Emotionally powerful,with an extraordinary sense of color, drama, and design, the artist describes his painting style as “Afro-Nouveau” and describes it as artwork that “reflects not only my visions as a black man and the unique visions of black people, it represents visions we all share regardless of the color of our skin. Emotions like hope, love, tenderness, faith, and serenity know no boundaries.” In the image above a powerful, winged beast pensively gazes out at a rushing waterfall while a flock of white birds pass by, undisturbed. Its intentions are unclear…dare we disturb it to find out?

Cyril Van Der Haegen

Contemporary artist Cyril Van Der Haegen has provided illustrations for an impressive number of board games, and numerous Magic the Gathering and WOW cards. His work is a fascinating combination of vivid, luminous color against grims shadow-shrouded settings, such as this malevolent menagerie of monsters closing in upon a lone adventurer, his lantern aloft, a faint, flickering shield against the encroaching dark.

Sand Worm from Dune, Alexey Shugurov

In contemporary fantasy artist Alexey Shugurov’s work, we are treated to an up-close visit with one of the colossal sandworms of Arakkis from Frank Herbert’s epic Dune. Based on the dragons from mythology that typically guard over some type of treasure, found in such stories as Beowulf and Jason and the Golden Fleece, the sandworms and the space travel “spice” they produced were more or less a plot device to get Paul Atreides where he needed to–that being a state of superhuman ascension. Herbert believed that a memorable myth must have something profoundly moving –a force dangerous and terrifying and yet also somehow essential–that could either empower the hero or overwhelm him completely.

Monstress, Sana Takeda

In the epic fantasy comics series, Monstress, Japanese Hugo and Eisner Award-winning illustrator and comic book artist Sana Takeda brings to life a dark world struggling with the aftermath of a war between humanity and supernatural forces, wherein teenager Maika Halfwolf shares a mysterious psychic link with a violent monster. An entity that takes over both her body and mind, the demon is a source of great power, but presents a terrible struggle for Maika to understand, reconcile with, and control. These twisted realms of magic and chaos are richly imagined and mesmerizing, with creatures that are bring-you-to-tears adorable and terrifying–in marvelous different ways.

The Favorite, Omar Rayyan 2010, oil on panel

Omar Rayyan has illustrated children’s books, provided art for Magic: The Gathering, and helped to create the look for the motion picture The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. His work, steeped in rich, fantastical narratives and the sumptuous settings of old-world aesthetics, draws inspiration and guidance from the great oil painters of the Northern Renaissance and the Romantic and Symbolist painters of the 19th century. Those expecting to see the traditional portraits and classical subjects of a bygone era may be in for a shock! I think it’s a fun shock, though. Rayyan’s canvases frequently depict whimsical interminglings of animals and humans, and, well, whatever this little beastie pictured above is, in endearing imaginings of companionship and camaraderie. This adorable little girl and her darling favorite even have matching flowers in their hair. Twinsies!

The Faith Militant, Tim Durning

Drawing inspiration from his love of nature, light, and pattern, contemporary artist Tim Durning works as a freelance illustrator for clients in the editorial, publishing and game markets. This appreciation for form and illumination can seen in cards and illustrations for the Game of Thrones card game, with the rainbow sword and seven-pointed star of the book’s Faithful Militant faction portrayed as a stylized stained glass window. The Faith of the Seven, often simply referred to as the Faith, is the dominant religion in most of the Seven Kingdoms in George RR Martin’s Game of Thrones series. Members of the Faith worship the Seven Who Are One, a single deity with seven aspects or faces. Their Sacred Scripture is called The Seven-Pointed Star.

Tiamat, Tyler Jacobson

In contemporary artist Tyler Jacobson’s work, you will find the drama of fantastical cinematic moments, brilliantly captured and frozen majestically in time. An award-winning illustrator whose work has been featured in magazines, games, and books, Jacobson combines intensely vivid colors, intriguing depths of chiaroscuro, and magnetic composition in the thrilling scenes he creations, such as the massive, 5-headed supremely powerful draconian goddess Tiamat, here. Tiamat is the queen and mother of evil dragons and a member of the Dungeons & Dragons pantheon whose name is taken from Tiamat, a primordial goddess in ancient Mesopotamian mythology.

Dinosaur Race, John Pitre

Fantasy painter John Pitre materializes entire worlds completely from his imagination, wielding his expressive paintbrush as an instrument of powerful social commentary. Uniting celestial and terrestrial aspects in otherworldly surroundings, the artist establishes a sense of balance and unity between living creatures and their strange planetary surroundings. The Hawaii-based artist’s fantasy canvases echo the real life issues that concern today’s society, including “the threat of overpopulation, the ominous shadow of nuclear war, and the ecological deterioration of our planet.”

Rat people in the Vaulted Chamber in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, illustrated by Chris Riddell

This strikingly atmospheric, painstakingly detailed black-and-white line art by contemporary artist Chris Riddel depicts ‘London Below,’ the fantastical underground counterpart of the modern city of London in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere. Drawing on the irresistible fascination and morbid curiosity we all have with places of dark, sooty, griminess–subways, sewers, and dark alleys, and mysterious openings to places that are forbidden to us, and perhaps growing out of a wondering what happens to the city’s less fortunate who slip beneath the radar and fall through the cracks of modern life, this is imagery that conjures the feeling of a community fading and forgotten, buried under so much dust and neglect.

The Metropolis of Tomorrow, Hugh Ferriss

Visionary American architect and master of shadow and light Hugh Macomber Ferriss (1889 – 1962) believed that skyscrapers were the product of a culture devoid of spirituality, and yet the man is now perhaps best known for his drawings of brooding, coldly alien skyscrapers. And if that rings a little strange, even more strange how, though Ferriss evidently never designed a single noteworthy building, it was observed after his death that “he influenced a generation of architects more than any other man.” This inspiration trickles down to influence popular culture, in the elaborate spires and looming silhouettes that piece the Gotham City skyline.

Paris of the Future, Moebius, Serigraph

The influence of French artist, cartoonist, and writer Jean Giraud/Moebius’ (1938-2012) signature blend of relentlessly imaginative psychedelic fantasy and surrealism stretches as far as the vast, strange horizons of his incredibly heady works. Contributing storyboards and concept designs to numerous science fiction and fantasy films, Giraud also co-founded Metal Hurlant (translated in English as Heavy Metal) in 1974, a magazine, unlike anything else at the time, and which revived a genre that had been dismissed by critics. The colorful, ecstatic optimism of the futuristic view of Paris, observed both by us, and four onlookers surveying from up high, beautifully illustrates the Antoine de Saint Exupery quote (inscribed beneath their vantage point) which reads: “The future is not to be predicted, but to be permitted.”

A typical city courtyard with a fountain envisioned by Phillipe Druillet

Known for his explosively detailed panoramic vistas and epic architecture, Philippe Druillet created wildly innovative ways to tell fantastical stories in comic format. Rife with wildly decorated armor, weapons, spaceships, immersive landscapes, and colossal statuary, and detailed to the point of delirium, the more one is drawn into one of his often full-page illustrations, the more one’s mind is thoroughly boggled.

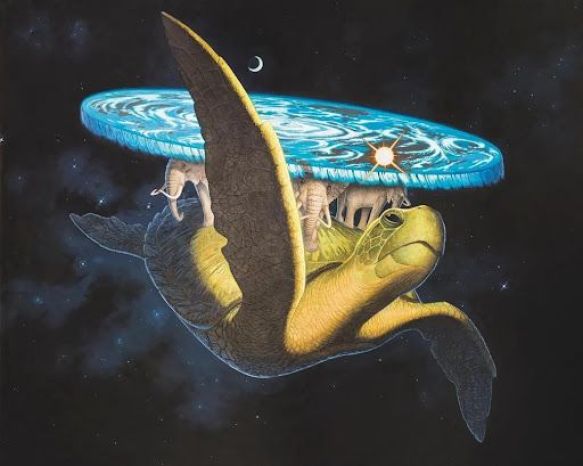

The Great A’tuin, Paul Kidby

Sir Terry Pratchett was the author responsible for a splendid cannon of literature including the celebrated Discworld series of 41 novels. Great A’Tuin, is the gigantic turtle upon whose back the Discworld was carried through space, although, to be precise, the Disc does not rest directly on A’Tuin; instead, it rests on the shoulders of four immense elephants, Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon and Jerakeen, who stand atop the turtle’s shell. Many things remain unknown about Great A’Tuin; these were matters of constant speculation by philosophers, mystics, and theologians. Nobody knows where it goes, or why, except probably Great A’Tuin itself. Paul Kidby (b.1964) was Pratchett’s ‘artist of choice’ for the award and has designed the ‘Discworld’ book jackets since 2002.

Earthsea, Rebecca Guay

In Ursula K. Le Guin’s coming-of-age story, A Wizard of Earthsea, we meet Ged, who as a wild and proud young wizard makes a terrible mistake. A major theme in Le Guin’s created world is the ethical and proper use of power; all inhabitants of Earthsea are aware of something called the Equilibrium, and maintaining the Equilibrium means maintaining the pattern and the order of the Earthsea universe. Lush and emotionally charged with vivid languor Rebecca Guay’s Earthsea artwork strikes a compelling balance between the classical and the surreal.

Kushiel’s Dart Donato Giancola

Painter of breathtakingly realistic imaginative narratives, Donato Giancola balances modern concepts with historical inspirations to create mesmerizing works bridging the worlds of the contemporary and the classical. In this anniversary edition of Jacqueline Carey’s epic fantasy Kushiel’s Dart for the Science Fiction Book Club Giancola has rendered gods-marked courtesan-spy Phèdre nó Delaunay de Montrève lush in every way an incandescent vision in deep scarlet sangoire, blood spilled by starlight. In Terre d’Ange, where all forms of love are considered sacred, “Love as Thou Wilt” forms the basis of D’Angeline religious belief. Moving in a world of cunning poets, deadly courtiers, heroic traitor, Phèdre trained equally in the courtly arts and the talents of the bedchamber, stumbles upon a plot that threatens the very foundations of her homeland.

The Amazon queen Penthesilea, Alan Lee

The daughter of Ares and queen of the legendary Amazons, Penthesileia was a bold, heroic character who famously led her troops to Troy in support of King Priam during the Trojan War. Said to have accidentally killed her sister Hippolyta, it’s possible that Penthesileia was seeking redemption in honor of a warrior’s death, which tragically came to pass at the hand of Achilles in the battles that ensued. Penthesilea’s story is a fascinating study of grief and fate and destiny; just a glimpse into her frank gaze in this haunting watercolor by Alan Lee, and you know that where she’s headed–she doesn’t intend to return.

A New Hope, The Brothers Hildebrandt

Greg and Tim Hildebrandt, known as the Brothers Hildebrandt, worked collaboratively as award-winning fantasy and science fiction artists for six decades, creating illustrations for some of the most influential comic books, movie posters of a generation–everything from their world-renowned poster for Star Wars to the best-selling calendars illustrating J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Their imaginations stirred by by comics, stoked by science fiction novels and films, and influenced by illustrators N.C. Wyeth and Maxfield Parrish, their dynamic, delightful works are forever favorites among fans.

Jor-El and Lara Lor Van, Nico Delort 2016

An illustrator working out of Paris, France, Nico Delort creates magnificent pen and ink compositions on their preferred medium of scratchboard, drenched in dramatic lighting, teeming with intricate detail, nuance, and evocative storytelling. In this dramatic work created for French Paper Art Club, we observe with hushed awe the hero Superman is in his Fortress of Solitude, hovering reverently before the miniature city of Kandor, last remnant of Krypton, and the giant statues of his parents, Jor-El and Lara Lor-Van.

Lucid Dreaming for Magic the Gathering, Nils Hamm

What if you could shape your dreams in whatever way you please? Lucid dreaming refers to a special type of dream where you’re consciously aware that you’re dreaming and during which time the dreamer may gain some amount of control over the dream characters, narrative, or environment. What fun! Personally, I’d eat a lot of jelly donuts and go on wild shopping sprees,, but with lucid dreaming, the only limit is your imagination, so your mileage may vary! In this Magic the Gathering sorcery card illustration by Nils Hamm a player can draw X amount of cards, wherein X is the number of card types in your discard pile. In this lovely bit of fantasy-inspired whimsy, the things you’ve lost along the way work toward granting you a small measure of control in obtaining things that might behoove your future plays.

Labyrinth movie poster, Ted Coconis

The legendary Ted Coconis has been painting and drawing for over 70 years and capturing our imaginations (well, I speak for the Gen X imaginations, at any rate) with pencils paint and ink, art, ever since we were children. Weaving together sensuality, emotion, memory, and fantasy has appeared in every major magazine and has been featured on dozens of iconic book covers and movie posters such as The Princess Bride and, of course, the hyper-gorgeous, ultra-memorble visuals for Jim Henson’s dark-hearted childhood dream, Labyrinth.

Little Nemo tribute: Dream Another Dream, Toby Cypress

Little Nemo in Slumberland was a full-page weekly comic strip created by the American cartoonist and animator, Windsor McCay in 1905. In each installment, a boy named Nemo dreams up an adventure which always ends with him waking up at home, in bed. We begin with King Morpheus of Slumberland commanding one of his Oomps to bring Nemo to Slumberland and eventually learn that Nemo has been summoned to be the playmate of Slumberland’s Princess–although this dream-quest is constantly interrupted. In contemporary artist Toby Cypress’s gloomy, glorious tribute, the delirium of Nemo’s dreams abound.

The Sandman, Yoshitako Amano

Yoshitaka Amano’s ethereal paintings of magical creatures, spirits, goblins, and apparitions have been praised and admired the world over, with influences that include Western comic books, art nouveau, and Japanese woodblock prints. The artist has won awards for his work, including the 1999 Bram Stoker Award for his collaboration with Neil Gaiman, Sandman: The Dream Hunters. Featuring striking painted artwork, this love story, set in ancient Japan, tells the story of a humble young monk and a magical, shape-changing fox who find themselves drawn together. As their romance blooms, the fox becomes aware of demonic intrigues threatening the life of her love; with the help of Morpheus, the King of All Night’s Dreamings, the fox must use all of her wiles to thwart the evil scheme. Written for the tenth anniversary of Sandman, it was no fairy tale adaptation, as some believed, but rather an original story posing as an adaptation, with Gaiman himself providing the misdirection in the form of an unreliable Afterword in which he cites his cheeky, fabricated sources.

If you would like to support this blog, consider buying the author a coffee?